Salt in the Blood

Wreckers, Smugglers, and the Ghost of John Bursey: A Salt-Stained History of Blood, Law, and the Coast That Ate Them All

Barton Shore, Barton Bones

Where the land forgets its own name and keeps trying to throw itself into the sea.

I live where the sea gnaws at the cliffs. Barton. Barton-on-Sea, where the cliffs rot faster than they should, where every storm pulls another slice of land into the tide. I’ve surfed here for 20 years, longboard mostly now, gliding over waves when they’re kind, dragged under when they aren’t. I photograph here too, salt on my lens, gulls shrieking like old ghosts.

And every time I paddle out, I think about bones in this ground. Family bones. Bursey bones. My own blood, John Bursey, murdered not far from here.

The story sits in me like ballast. He was a Riding Officer, an early coastguard, sworn to stop the smuggling gangs who stalked this coast. He walked out one night in 1780 and never came home. Beaten to death, his wife threatened with gunfire. The smugglers left no names. Just bruises, silence, and a headstone in St Mary Magdalene’s church at Milton.

That’s the sober part. But the sea never lets things stay sober. Every family story corrodes in salt until it starts to sound like myth. Sometimes I wonder if I see him still, on foggy nights, a lone rider on the cliff, lantern swinging, eyes hollowed out by tide and time.

This isn’t just a family story. It’s a coastline story. Barton. Milton. Mudeford. Hartland. Devon, Cornwall, Dorset. Places where law frays, where wreckers and smugglers made their living from other people’s deaths. Where the cliffs still hum with voices if you stand there long enough.

And this is my attempt to tell it. Not clean, not polished, but the way the sea tells stories: layered, half-true, half-dream, and all of it salted.

Part I — Wreckers and Rocks

Men lit false stars and called it mercy.

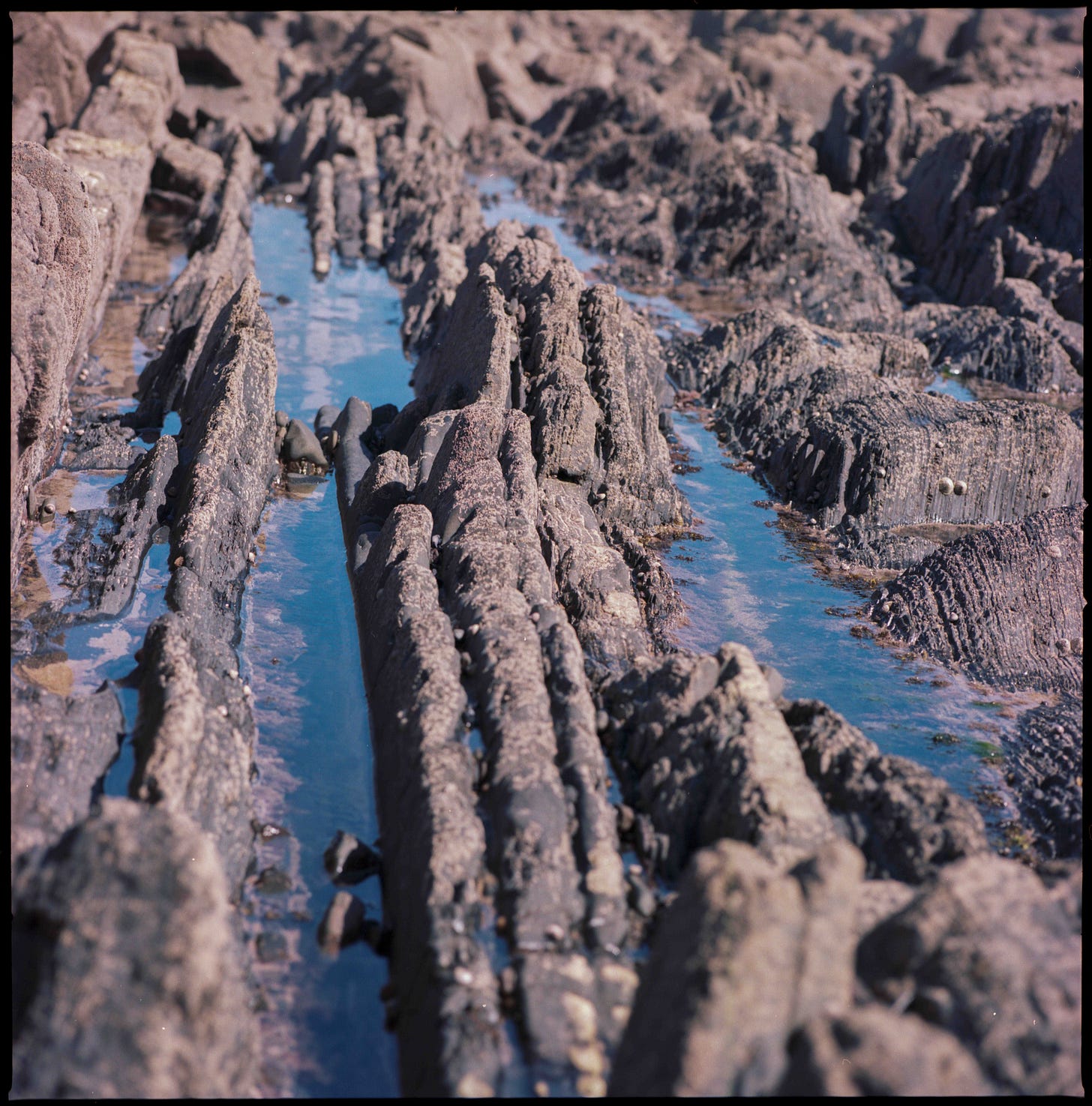

Like a broken mast and a torn sail from the violent edge of the Atlantic, Chapel Rock stands alone at Hartland Quay. A sentinel of dark stone and myth, it watches the tides roll in and out with the indifference of something that has seen too much. Its spine juts toward the horizon like a warning, or an accusation.

The coastline that surrounds it is The Wrecker’s Coast. Ragged, sharp, and haunted. The Atlantic doesn’t break here; it attacks. Swells roll in from the Americas, gathering for a thousand miles, and detonate against these cliffs with the weight of continents. The air tastes of iron and salt, the wind carries voices if you let it. Even the gulls sound older.

More than 150 wrecks have been recorded along this short stretch. Ships splintered into bone and cargo by reefs with names like Teeth, Blackpool, and Screda Point. Others lie unrecorded, nameless skeletons crushed into sand. On storm nights, when the tide drags hard and the wind goes hollow, the sea still spits up their ghosts; brass fittings, shards of glass, fragments of rope worn down to threads of salt.

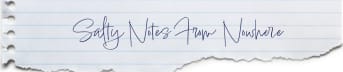

The cliffs rise near-vertical, 300 feet of layered slate and sandstone folded by time into something that looks half-organic, like the ribs of the world left bare. Below, the shore is a chaos of boulders slick with weed, the kind that slide underfoot like betrayal. Walk there at low tide and you’ll find yourself between ages, rock older than language, sea forever young and cruel.

Hartland has always been a frontier, the last hard edge before Cornwall gives itself to the sea. The Romans never settled it. The Saxons called it Heretlan — “stag land” — wild and untamed. Even the church at Stoke, inland and ancient, feels like an outpost clinging to faith by its fingernails. The locals used to say the devil built the cliffs himself, piling them high to keep out the light.

There’s a loneliness to this place that doesn’t feel empty. Every gust carries memory of sailors praying to St. Nectan, of wreckers waiting with their false lights, of waves booming in coves too deep to name. The rocks hold those prayers still, sealed inside their layers. And when the sun sets red over the Atlantic, the whole coast seems to breathe. One long exhale from the sea that never forgives and the land that never yields.

Before charts were clear, before lighthouses lit the fog, the rocks wrote their own maps. And men, greedy or starving, made use of that. Lanterns tied to donkeys, walked along cliff paths to imitate safe harbour lights. A cruel trick: the ship followed the glow, thinking it was salvation, and found only ruin.

The cargo was stripped by torchlight. Bodies, if they were buried, were buried shallow. Just inland lies the churchyard of St Nectan’s, where the nameless dead from wrecks were laid. No stones. No markers. Just the salt-heavy wind. Some nights the villagers swore they heard hulls groaning, bells tolling faintly in the mist. Maybe grief. Maybe guilt. Maybe the sea never forgets.

Not all wreckers were wolves. Some were rescuers. Men who climbed cliffs in storms, who launched boats into black water to drag strangers out of the surf. Hartland Lifeboat Station once stood as proof of that refusal — the human urge to resist the sea’s appetite.

But still, Chapel Rock remains. A jagged altar. A place where prayer is swallowed by wind. Sailors used to say the sea “reaches for Hartland with both hands.” Chapel Rock is the finger. Pointing at danger. Pointing at history. Pointing at every loss the tide has kept.

The Wrecker’s Playbook

How to drown a stranger and call it navigation.

(A few of the old tricks, whispered down the coast, best read with salt in your mouth and one eye on the horizon)

The sea was never cruel enough for some men. Storms and reefs took their share, but wreckers wanted more, and so they made their own storms. You’ll hear it said, down in taverns, in the back pew of churches, even whispered in the salt wind: not every wreck was the sea’s doing.

Lanterns on Donkeys

Tie a lantern to a donkey and send it walking the cliff edge. From a mile out, in fog thick as milk and prayer, it looks like a harbour light swinging gentle and true. The sailors see salvation and steer straight for it. By the time they realise the light’s moving wrong, the rocks are already sharpening their teeth. The keel cracks, the mast screams, and the donkey just keeps walking. The beast doesn’t even know it’s a murderer, and the men who sent it don’t care.

False Beacons

Bonfires on headlands, torches in neat, deceitful rows. Imitation harbours, counterfeit mercy. Out there, on the black swell, a watchman squints through salt and sleep, sees the flames, and thanks God he’s almost home. He’s not. He’s heading for stone and splinters, for the sound a ship makes when it learns it can die. The wreckers wait above, silent, blades tucked against their sleeves, ready to take communion in brandy and blood.

Extinguish the True Light

The bold ones killed real light. Doused lighthouses, snuffed lanterns, and raised their own false stars. Picture it: fog so thick you could drown standing still, and then, there, a glow where there should be one. Familiar. Comforting. Except it’s not safety. It’s appetite. Hunger wearing fire as a mask.

Bells and Horns

Not every lie burns. Some toll. Some moan. Wreckers learned the language of sound, hung their own bells, blew their own horns, called ships home like sirens in the dark. A captain hears the rhythm he trusts, turns toward it, and listens all the way to his death. When the sea closes over, the wreckers haul in the silence and call it profit.

Painted Stones, Carved Landmarks

Some cliffs were painted. White crosses, false markers, holy lies. Others were carved, reshaped, made to mimic the safe signs on every sailor’s chart. A man at the helm, aligning two headlands by moonlight, thinks he’s steering for life. He isn’t. He’s steering straight into his own elegy.

Buoys Moved by Night

This is the darkest trick of all. Buoys don’t lie, until men make them liars. A channel marker shifted fifty yards is a murder weapon. Dragged through the surf by hands that smell of rope and sin, it remaps the sea, turns haven into hell. The captain swears he followed his charts, and he did. He just didn’t know the sea had been rewritten in the dark.

Some say these are just tales, the paranoia of sailors drunk on fear and brandy. But walk the churchyards near Hartland or Barton, see the rows of nameless dead, and you’ll know. Too many bodies came ashore for the sea to blame alone.

Part II — Smuggling in Hampshire

Every parish had a secret and a shovel.

The wreckers belonged to Devon and Cornwall, but here in Hampshire and the New Forest the trade was smuggling.

“Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark –

Brandy for the Parson, ‘Baccy for the Clerk.

Laces for a lady; letters for a spy,

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!”— Rudyard Kipling.

It wasn’t Robin Hood romance. The smugglers weren’t folk heroes. They were organised criminals, ruthless and armed. Brandy, tobacco, tea, silks — brought across the Channel in fast vessels, chased by Revenue cutters. If they outran or outfought them, they made for landing places like Chewton Bunny, Becton Bunny, Taddiford Gap. Even Hurst Castle, where the garrison once colluded with them, sheltering contraband in stone walls that were supposed to defend the Crown.

On the Isle of Wight—just across the channel from our shores—smugglers didn’t always need shadows. They hauled tubs of brandy up cliffs with ropes… literal cliffhangers. Imagine those rope lines straining under contraband, high above the waves, waiting for a slip. When the cargo tumbled down, so did the blame—and none of it ever washed ashore.

Once ashore, goods vanished into the forest. To the Cat and Fiddle at Hinton. The Queen’s Head at Burley. Safe pubs. Safe barns. Smuggling routes hidden like veins under the skin of the land.

The gangs were huge. Well-armed. Violent. The Excise men called in militia from Lancashire just to stand a chance. Battles flared. Mudeford in 1784, Milford Green a year or two later. Smugglers on horseback, Revenue men outnumbered, shots fired, men left dead in lanes.

Fear seeped into the villages. Informers killed. In 1780 a Barton woman was asphyxiated in her house — doors and chimney sealed with wet cloth until the air ran out. This was not adventure. This was terror.

And in the middle of it: John Bursey.

Part III — The Night They Came for Bursey

No man ever drowned who wasn’t already thinking of someone.

Milton, Hampshire — 25 August 1780, about 1 a.m.

They came to the house with a lie and with clubs.

Five men, unknown; the pretense was information—“contraband landed, sir, we can show you.” John Bursey, Riding Officer of the Customs, got up out of bed. He opened his door. They rushed him. Clubs, “other offensive weapons,” blows to the head and to “other parts of his body,” and the kind of beating that leaves a man lingering between this world and the next. When his wife tried to raise the alarm, a shot cracked the dark. He lasted “till the 28th, and then died.” The coroner’s jury called it murder. The Custom-House offered £100 for names.

That’s the official language. The unofficial version is simpler: in a village that knew every footpath and lantern code, Bursey was the man who wouldn’t look away. On a coast where everyone owed someone, he owed the Crown—and paid for it at his own front door.

The 1780 Custom-House Notice (clean transcription)

Custom-House, London, Sept. 30, 1780.

Whereas, on Friday the 25th of August last, about One of the Clock in the Morning, five Persons unknown, armed with Clubs and other offensive Weapons, came to the House of John Bursey, late, a Riding Officer of the Customs, at Milton in the County of Southampton, and, under Pretence of giving the said Bursey an Information, whereby he might make Seizure of some uncustomed Goods, prevailed on him to get up (the said Bursey being then in Bed) and to come down and open his Door; that they thereupon immediately rushed in upon him, and with the said Clubs and other Weapons beat and treated him so inhumanly, by giving him several dangerous Wounds about the Head and other Parts of his Body, that he languished till the 28th, and then died; and the Coroner’s Inquest having brought in their Verdict Wilful Murder against the said five Persons unknown: The Commissioners of His Majesty’s Customs, in order to bring the Offenders to Justice, do hereby promise a Reward of ONE HUNDRED POUNDS, to any Person or Persons who shall discover and apprehend, or cause to be discovered and apprehended, any one or more of the said Offenders; to be paid by the Receiver-General of His Majesty’s Customs upon Conviction.

— By Order of the Commissioners.

Part IV — John Bursey, Riding Officer

The King’s ghost-dog, walking alone with a pistol and a prayer.

From Milton you had four ways to the sea. Southern Lane to Barton Lane past the Coastguard cottages. Southern to Moat, then southeast across Barton into Dilly. Due south along Farm Lane to join Dilly near Barton Farm. Or east along what was Barton Road. In 1780 they were tracks, not roads—good enough for a pony, bad enough to swallow witnesses. The Tithe map says who owned what; the parish records say who lived long enough to pass it on.

He died the way these coasts teach you to die: slowly, with neighbors listening behind shutters. Three days. Bruises flowering under the hair, a skull gone tender, breath rattling like shingle. In the ledger he’s a line item—“late, a Riding Officer”—but on Barton clay he’s a husband who opened a door because duty knocked with the voice of information.

He was no ordinary coastguard. The Riding Officer lived on the edge—isolated, watchful, threatened until death. John Bursey’s example was grim proof of how fragile law was when the sea called men to darkness.

Riding Officers were less men than shadows on horseback. Commissioned from 1690 onwards, they patrolled ten miles of coast and five miles inland, one man against gangs of fifty. They bought their own horses, sabres, pistols, even the paper for their reports. Pay was poor, £90 a year, and company scarcer still. Their “uniform” was rain-soaked coats, tricorne hats gone thin, boots rotted from salt.

They were tasked with everything: watching for lantern codes, recording landings, chasing smugglers, even scanning for French invasion. They carried flintlocks that misfired as often as they saved them, sabres more promise than defence. At night they wrote their journals — seizures, patrols, suspicions — records that survived longer than they did.

Some were corrupted. Some looked the other way. Too many ended like Bursey: lured from their own door by lies, beaten until their skull split, their wives left to fend off bullets in the dark.

To villages, they were “the King’s ghost-dogs.” Hated for their allegiance, pitied for their loneliness. You’d see one ride past at dusk, pistol glinting faintly in lantern light, and know he was either a fool or a corpse-in-waiting. Children whispered they weren’t men at all, but half-dead watchers who’d be found face down in surf, horses still waiting on the cliff.

Bursey was family. He was also a warning: the coast doesn’t forgive loyalty.

“The silence of the snowy night

Is the death of the world.”

— Georg Trakl (translated)

Part V — Cornwall, Devon, Salt Roads

Salt knows. It keeps the dead fresh.

I’m at Hartland Quay now. The camera hangs heavy, straps digging into the back of my neck, damp with salt and sweat. The surf booms against Chapel Rock like it’s knocking on the door to something older than language. The sky’s the colour of wet slate, the kind of grey that eats the horizon. This isn’t Hampshire. This is Devon, Cornwall’s jagged shoulder. The Wrecker’s Coast. A place that feels more like home than home.

The tide chased me down the rocks earlier — one bad step, one wave higher than it should’ve been. Tore the sole clean off my boot. Now every step slaps cold and uneven against stone. My legs ache from miles of scrambling boulders slick with weed, crawling over slabs of fallen cliff that shift and groan under my weight. I duck into caves slick with saltwater, my breath loud, camera held tight like a relic. Inside, the air smells of rot and old storms, of something that never dried.

The wreck of the SS Rosalia still lies out there, ribs of iron rising at low tide like something trying to breathe again. She went down in 1912, iron to iron, wave to wave, and she’s still breaking, even now. I press the shutter, no screen, no forgiveness, just glass and film and whatever light the coast offers.

Film belongs here. Ilford FP4. Kodak Ektar. Stocks that punish mistakes and reward patience. Grain sharp as salt. Shadows that bite back. Digital would polish this place, bleach it clean, erase the noise that makes it real. But film? Film leaves the wounds visible. It shows the smear of rain on the lens, the ghost of a wave that moved too fast, the tremor in your hands when the wind hits hard.

Loading film in the wind is a kind of prayer. Rain slanting sideways, poncho flapping like a torn sail, fingers stiff and slick with salt. The camera’s open throat catches every drop and I curse, but I keep going, trying to shield it with my body, hunching over it like a dying fire. In the caves it’s worse; water drips from the ceiling in cold, slow pulses, finds its way down the back of my neck and settles between my shoulder blades like guilt. I set up the little petrol stove on a flat rock, flame guttering, boil water, pour the coffee. It tastes of smoke and iron and damp, and it’s perfect. The ritual keeps me sane. Film loaded, coffee made, sea breathing just beyond the dark. I wouldn’t change a thing. Not the rain, not the cold, not even the ache in my legs. Maybe just the boots. I could do without the boots giving up halfway through the day.

When I get home, I’ll load the reels in the dark, fingers numb, the smell of developer thick as iodine. The film will curl like seaweed in the tank. Light turned liquid, silver bleeding through the emulsion. I’ll watch the negatives bloom under red light, each frame surfacing like a body through fog. Some will fail, overexposed, streaked, ruined by salt that crept into the seals. But the ones that live will carry the coast inside them: the hiss of rain, the echo of rock, the memory of a man standing alone with the sea beating its hands against the door.

The coast doesn’t soften itself. Neither does film. Both strip you down until all that’s left is what endures. The scar, the grain, the salt that refuses to leave.

Each frame is more than a picture. It’s a silence. A bruise. A record of a moment already lost. The wind tears history out of the cliffs while the shutter tries to trap it. It won’t last. Not the negative, not the wreck, not the names carved shallow in St Nectan’s yard, but maybe the scar will. Maybe the salt will.

Cornwall and Devon are full of those scars. Every cove is a grave. Every headland has seen the glint of false lights, the lie of safe passage. Smuggling routes run inland like veins. From Hartland to Boscastle. Tintagel to Padstow.

And me, with my camera, I’m just another scavenger. Another man picking at what the tide couldn’t quite pull back.

Part VI — Salt and Film

A ship is a coffin with a view.

I walk the same lanes John Bursey once rode: Southern Lane, Moat Lane, the old Farm Lane down to Dilly. The names are softened now. The work isn’t. Ghosts are reliable here, some wear uniforms, some carry contraband, some knock at the door pretending to be friends.

When I frame a shot along a coast, I’m really framing a family ledger: a murdered man, a reward never claimed, a coastline that still punishes loyalty.

“The tide flows and ebbs, but the rock remains.

I too am of that rock.”

— Robinson Jeffers

I’ve photographed wrecks before. Sometimes, on slow ISO film, the Ilford backing paper bleeds through — ghost text floating faint across the image, like something printed by time itself. It ruins some frames. It blesses others.

Maybe these coasts are the same. The past bleeds through, not all at once, not always clearly, but there in the grain. John’s death. The wreckers’ tricks. The quiet complicities. Like flaws you can’t quite edit out.

At Barton, when the surf folds over my head, I wonder if the waves remember. At Hartland, I level the lens and feel the rock staring back.

The camera doesn’t care that this cliff will fall. Doesn’t care that this sand was once stone, or that salt works slower than fire but finishes the job just the same. But I care. I point the lens like a question, asking the sea what it remembers. What it’s still hiding. What it’s trying to erase.

Photographing the coast is an act of surrender and defiance at once. You frame the quiet, the ripple, the stillness, knowing the next wave is already on its way to undo everything. Erosion is the true artist here. You’re just trying to steal a copy before it vanishes.

Some days the sea is cruel. You line up a shot, crouch into the wind, fire — and by the time the shutter closes, the moment is gone. That rock won’t be there in ten years. That cliff behind you is bleeding into the tide. And the sand under your boots was someone’s farmland once.

But the sea is generous too. Some days she gives you light so soft it feels like forgiveness. Some days she goes still, just long enough to let you catch your breath. But the danger’s never gone. It’s in the undertow. In the frayed edge of a wave. In the knowledge that everything you’re capturing is already halfway gone.

Part VII — The Smuggler’s Gospel

The light was false, but we followed it anyway. We always do.

Here’s the truth about smuggling: it was survival. It was cruelty. It was crime. It was community. It was all of it, tangled.

At Hurst Castle, the governor himself sheltered contraband. At Barton, locals joined gangs because saying no meant a beating. Smuggling was a business, not a romance. And business was bloody. Just inland, another branch of my blood once lived in a mud cottage beside the coastguard hut at Keyhaven. Sea on one side, duty on the other. Their roof tangled with creepers, their days lived next door to the very men trying (and often failing) to stem the tide of contraband. It’s not hard to imagine the stories passed through that wall, the warnings, the bargains, the silence. We were close to the sea, close to the law, and closer still to the salt line where one blurred into the other.

The militia fought them. The Coastguard was born from that fight. Uniformed men stationed on cliff tops, lanterns against the dark. The first station near Barton held seven men and one chief officer. Their job was simple: stop the tide of smuggling, or at least slow it.

But the gangs were clever. They moved by night, by pony, by cart. They used the forest as a cloak, the cliffs as allies, and the locals as unwilling lookouts. Contraband vanished into caves at Chewton Bunny and Becton Gap, barrels sealed tight against the tide and hidden behind seaweed and stone until the coast was clear. Up in the forest, they stashed goods in hollow oaks and turf cellars, in barns that smelled of hay and danger. From Milford to Beaulieu, from Boldre to Burley, the whole landscape was an accomplice — every glade a hiding place, every track a secret map known only to hooves and whispers.

Inland, the tracks still whisper the old routes. There’s a village called Tiptoe, just north of Lymington, said to have earned its name from the smugglers who wrapped the hooves of their ponies in sacking to soften the sound. Linguists will tell you it’s older than that, a Norman corruption of Tippetot—but I like the other story better. The one where even the horses knew to move quietly.

The New Forest wasn’t just a refuge, it was a partner. The gangs knew its moods, its paths, its blind corners. The trees themselves seemed to close ranks around them. You could walk a mile inland from the coast and still smell the brandy, still hear the distant clatter of kegs rolling through fern and fog. The law chased shadows. The smugglers walked with the trees.

They called it smuggling, but it was just the coast doing what it’s always done — feeding those who dared it. The sea doesn’t care about laws. She only rewards courage and punishes hesitation. Every cottage, every hut, every cliff path around here still hums with it — the sound of barrels rolled through fog, of men praying their neighbours kept quiet.

Even now, when the wind cuts right, you can hear them. Hooves on shingle, whispers in the hedgerows, the cough of a lantern going dark. The salt never left. It’s in the walls, the soil, the blood. We like to think we’re cleaner now — better, lawful — but the truth is, we’re still hauling something wet and forbidden out of the dark.

Kipling was right: “watch the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by.”

Salt in the Blood

John Bursey’s name is still carved in Milton. The smugglers who killed him are dust. His blood is mine.

I still live on the cliffs. I work on the water. I surf at Barton. I drag cameras to Cornwall, to the Wrecker’s Coast. I walk where smugglers rode, where wreckers lit their lies, where coastguards fought in the dark.

And I know this: the sea doesn’t forget. The land doesn’t forgive. And family stories don’t stay buried.

Salt in the blood doesn’t wash out. Not with time. Not with distance. Not even with death.

This signal only reaches you because I screamed it into the wind.

If anything in this mess stirred something in your chest cavity—a shiver, a laugh, a vague desire to hurl yourself into the sea and become a seaweed farmer with no online presence, you can:

Buy me a beer — fuel for edits, breakdowns, and Bob’s candle-making experiments.

Buy a print — fragments of light, shipped from the edge, packed by hand (and moth).

(It’s cheaper to just email me too)

Each order smells faintly of sea-salt, archival glue, and quiet desperation.

Bob insists on blessing the postage with a silica packet and a whisper.

The sea tries to take the shop back every full moon, but we hold the line—for now.

Support this strange, salt-bitten work, and I’ll keep sending dispatches from the shore: where the gulls scream, the film curls, and the light still feels like something worth chasing.

No pressure. No algorithmic guilt. This thing survives on rum, signal flares, sea ghosts, and the occasional kind soul who decides to throw a coin to the crumbling sailor yelling into the void. If now’s not the moment, that’s fine. Just don’t unfollow. Bob gets twitchy.

I am a sucker for birds just so... Your final image is superb. Thank you. Lovely post. You write this with such passion!

Loved every second of this. So cool that you know your family history so intimately and get to walk the same places they did. And I agree with Soren, that last shot is incredible.